This story is part of a UToledo Faculty/Staff Spotlight series, where we feature uplifting stories of the remarkable achievements and contributions of hidden champions who call the University of Toledo home, fostering connections across campus. Cover image by Caeley Powell for Juice House.

If you ask Dr. Robert Blumenthal why he wanted to become a microbiologist, he would tell you the decision began when he was three years old.

“My father was a microbiologist. Used to bring me into his lab, which now would get him arrested. But back then, there weren’t laws that prevent young children from going into labs,” said Blumenthal. The early exposure came from both directions: Blumenthal’s mother was a biochemist. “So, I sort of had it coming from both directions,” he said.

Seemingly, his career was set from a young age, but new interests attracted him as he got older that almost led him down a different path.

“When I got into high school, I found myself in a rock band,” Blumenthal said. His band recorded and released their very own 45 rpm vinyl record which aired on the radio for a short time.

Blumenthal’s love of music also led him to play the keyboard and sing in various choirs, but it was ultimately music that guided him back to his love of science.

“[T]he thing that stands out and played an important role in my going into science was up at Interlochen, at the National Music Camp,” Blumenthal said. Now called the Interlochen Arts Camp, Blumenthal attended a program there that his father had constructed.

“[In] the morning [students] would do orchestra, or choir, or theater, or dance or ceramics … And then in the afternoon, it was a microbiology program. And that sort of mix was magical for me,” Blumenthal said.

Fast forward to the fall of his freshman year, Blumenthal attended Indiana University to study microbiology. “When I was trying to make this decision about whether to go into music or microbiology …. one of the reasons I went there is …. it’s got a really good music school,” he said.

At this juncture, Blumenthal found his love for music leading him back to pursuing science. During his introductory music composition course, he unknowingly criticized the work of his professor — work that would go on to win the MacArthur Genius Award.

“Later that week, I’m coming out of the practice rooms and I see him in the hallway, and I say, ‘Professor Eaton, I think I need to talk to you,’” Blumenthal recounts. “[H]e was amused. And so he started talking to me and it turned out that he had been a biochemistry major as an undergraduate and was very excited that someone taking science courses was also taking his composition course.”

Blumenthal excelled in microbiology at Indiana University and continued his education at the University of Michigan where he got his Master’s and PhD. Then, continuing in the vein of science, he went on to have two postdocs; the first at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and the second in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island.

Not only was he extremely well educated in this field, but he also studied under lead scientists of the field. At the time Blumenthal was at Cold Spring Harbor, the director was James Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA and Nobel Prize recipient. Blumenthal worked in the lab of Richard Roberts, who was awarded a Nobel Prize for co-discovering RNA splicing, and his office neighbor was Barbara McClintock, who was also a Nobel laureate for discovering “jumping genes.”

“And then I came to what was then the Medical College of Ohio, back in 1981. And I’ve been here ever since,” said Blumenthal.

On the Health Science Campus, Blumenthal works in the department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology teaching graduate and medical students and running a research lab where he examines proteins in bacteria and their function in controlling genes. During his tenure here at the University of Toledo, he helped start the Bioinformatics program and ran it for 21 years. And, in 2012, he was appointed as a Distinguished University Professor for his research.

Blumenthal’s many achievements were greatly shaped by the influence of those alongside him in his journey as a scientist and professor from both music and science.

“I had two people who profoundly shaped my understanding of what a good teacher is, [and] neither of them were scientists,” he said. “One was a choir director that I had when I was at the National Music Camp … and the other was my drama teacher and director for several productions in high school.”

These teachers taught him the importance of striking a balance “where the class can be fun, but you learn a lot and there’s a certain amount of discipline, and there are lines you don’t cross. You know, and striking that balance between keeping control but letting everyone express their own style and have a certain amount of fun,” he said.

And from the research perspective, Blumenthal learned from the researchers he’s worked with over the decades the importance of not losing your sense of wonder and exploration, whether diving into a particular research focus or looking in many directions to find new things. In his own words, “there’s plenty left to be discovered.”

Although Blumenthal never made a career in music, now in his later years, his passion for it has come full circle. He shared that just this past January, a record label from England contacted him.

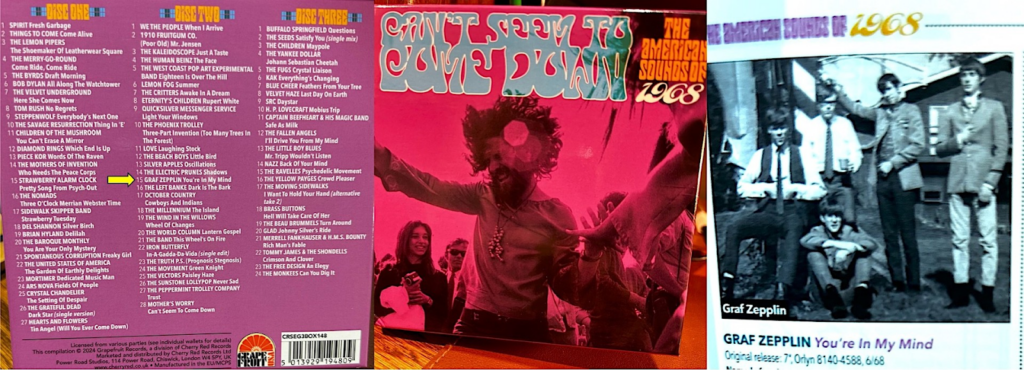

“[They] said, ‘We’re putting together a compilation of American rock music of 1968, and we wanted to include a couple of garage bands and we want to include yours,’” Blumenthal retells. “So I am on this compilation now, along with the likes of Bob Dylan, and the Grateful Dead, and The Velvet Underground, and The Beach Boys, and The Monkees, and Buffalo Springfield and many other bands … it’s certainly a big deal for me,” he said.

In the end, Blumenthal’s career wasn’t choosing microbiology or music, but a journey inspired by microbiology and music.