Although every person’s life experiences are unique, not every story is told. Some stories, like that of Holocaust survivor Philip Markowicz, are kept alive by those who take the time to recount them.

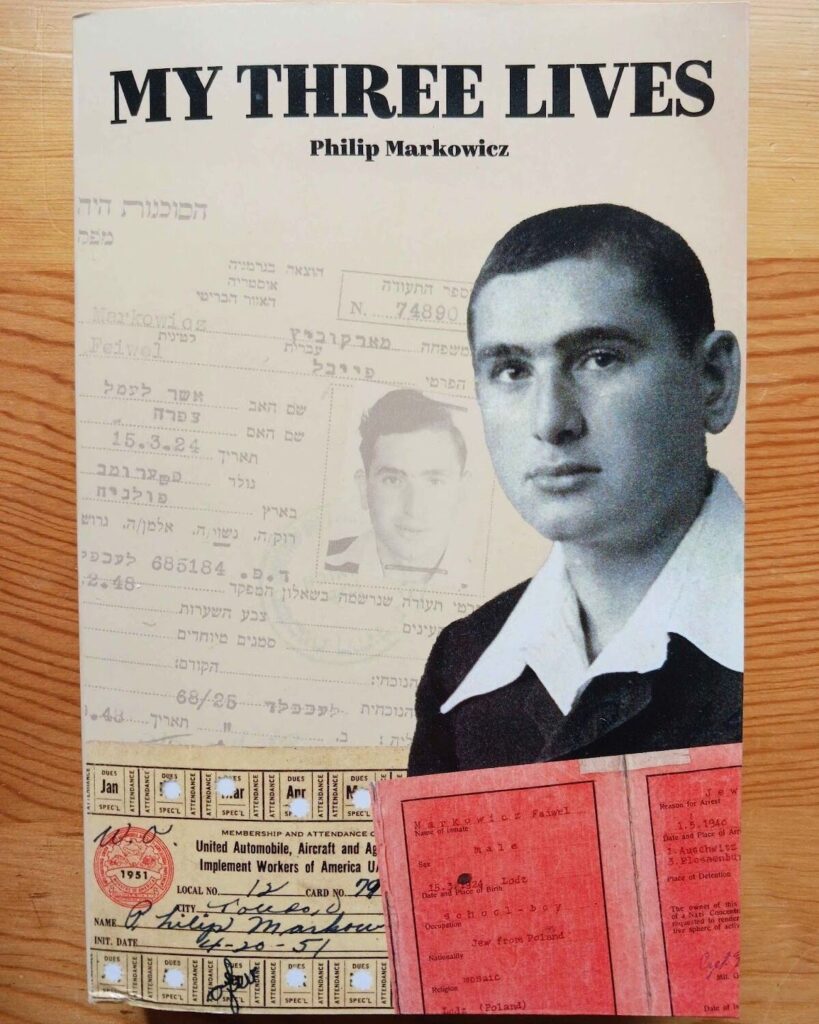

The UToledo community had the opportunity to hear Markowicz’s story on Jan. 29, 2025 as part of the Carlson Conversations Lecture Series. Markowicz, who had settled in Toledo after surviving the Holocaust, influenced the establishment of the Judaism and Biblical Studies program at the University of Toledo. Bridging his connection from his incredible past to his active involvement in the community and the university, he also wrote a memoir in 2009 about his life called “My Three Lives.”

Though Markowicz passed away in 2017, his grandson, Steven Markowicz, continues to share his grandfather’s story and was the speaker at the Carlson Conversations Lecture Series where he shared excerpts from Philip Markowicz’s memoir. He explained how his grandfather considered himself to have lived three distinct lives from his childhood to adulthood, segmented by World War II. Attendees intently listened throughout the talk, becoming familiar with one survivor’s story among many others.

“I’m telling only one story,” Steven Markowicz said. “There are millions of other stories to be told about the experiences of the survivors and their families.”

The impact of the talk was immediate upon the audience. Sam Ruff, a senior studying English at the University of Toledo who attended the event, shared how one person’s story revealed more about the Holocaust than she initially thought.

“I never considered any of that could happen, and all of the little details that I had previously not known,” she said. “I thought I would know them by now from history lessons, but you just can’t know unless you have a personal story.”

Through the lens of Philip Markowicz’s experiences as a young Jewish boy growing up in a small village in Poland, the audience was brought into the pre-World War II era, where family and faith played an integral role in shaping his life. He was born in Przerab, Poland, on March 15, 1924 into a large and very religious family. By 1938, Philip had enrolled in a private religious school in a larger city near his village.

“It’s hard to impress how religious the family was. Judaism, studying Torah, learning about the Torah was of utmost importance to the family,” Steven Markowicz said.

With the beginning of World War II came the end of this period of life for many like Philip Markowicz, and the beginning of his second, tragic one — a young Jewish man oppressed under the regime of Nazi Germany. The large city of Lodz provided temporary security, but Philip Markowicz and his family found themselves stuck in the Lodz Ghetto starting in February 1940. Within the ghetto, there was forced labor, overcrowding, barely enough food to eat and no way to get out. Families like Philip Markowicz’s struggled to stay together as people passed away or were forcibly removed from the ghetto and killed.

Philip was particularly close to his sister. She had a profound impact on his life by opening his eyes to the more secular aspects of life outside of the small, religious world he was born into. Steven Markowicz recounted an excerpt from his grandfather’s memoir about how he felt after discovering that his mother and sister were removed from the Lodz ghetto and killed by the Nazis in September 1942.

“Nothing affected my life as much as the knowledge of what happened to my dear mother, sister and little nephew on that cursed day,” Philip Markowicz wrote. “What really happened was so out of the sphere of reality that it was unimaginable that such a thing could ever take place.”

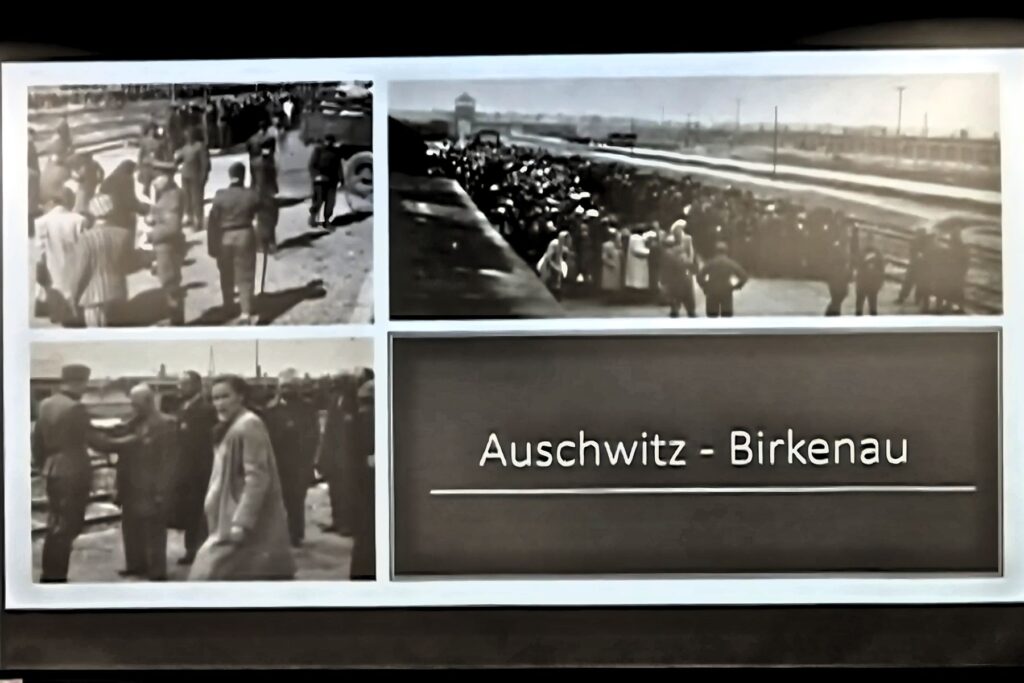

By August 1944, Philip and his brother, Henry, were the only members of his family left alive. Allied forces were advancing on Europe around this time. Philip and Henry were among millions of Jewish people sent to Auschwitz, a concentration and extermination camp in Poland. Philip Markowicz’s optimism, shrewd thinking and desire to keep himself and his brother alive were what allowed the two to survive.

Some survived through what may be considered miraculous events from the camps, such as those that contributed to Philip Markowicz and his brother’s survival. In one instance, prisoners who passed a full-body inspection by doctors would be taken out of Auschwitz on work detail. The brothers made a plan to get into the same work detail and escape together, as unlikely as that might be. Their opportunity came while a distraction interrupted work detail inspections.

“One day while this process was going on, there was a giant commotion. Everybody’s attention turned to what was going on. This process had already started. There were men in line, there were other men who were standing naked after having already been analyzed by doctors,” Steven Markowicz said. “When this commotion happened, Philip and Henry looked at each other, and without even saying a word, they stripped down all of their clothes and ran into the line of people who had already been examined by the doctor, hoping to mingle in and luck out. No one saw. So, thankfully, that’s how they got out of Auschwitz. A miracle.”

The brothers had escaped Auschwitz only to have arrived at another concentration camp. However, miracles continued to occur even as Philip Markowicz and his brother were moved around Europe. In one case known as the “miracle on the train,” a stranger on the train Philip Markowicz was boarding gave him his sandwich, which gave him enough energy to keep surviving. In another case, the brothers escaped into a barn with other prisoners while on a death march. Nazi soldiers were about to kill them until two women came into the barn and forbade the soldiers from killing anyone on their property. This event occurred just one day before Philip Markowicz and his brother were liberated.

Bobbie Miga, a community member and University of Toledo graduate in attendance at the lecture, was particularly struck by these miracles, and attributes them to Philip Markowicz’s faith.

“It was pretty evident to me that God had a plan for him. He was saved for a reason,” Miga said.

Philip and Henry Markowicz were liberated on May 4, 1945. After surviving the unthinkable, Philip Markowicz’s third life as a Holocaust survivor who rebuilt his life after tragedy began. Philip Markowicz met his wife, Ruth, in a displaced persons camp after the war and moved to the United States via a sponsor in Toledo. The two started a family that still has roots in Toledo to this day.

Stories like Philip Markowicz’s have continued to remain important into the 21st century. As the number of Holocaust survivors has decreased, it’s up to future generations to keep their legacies alive. Today, only 245,000 survivors remain in the world, according to estimates, with nearly 16% residing in the U.S. One way of keeping their stories alive is by having the descendants of Holocaust survivors become interested in telling these stories. Steven Markowicz is a part of 3GNY, a New York-based nonprofit dedicated to providing support for the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors and fostering an interest in the stories of their grandparents.

“The number of Holocaust survivors that are left are dwindling to the extent that there’s barely any left, and even those that are here are very young,” Steven Markowicz said. “They don’t have as much of the information as, for example, that my grandfather would have after being somewhat of an adult going through the war.”

Another critical way of ensuring knowledge of the Holocaust is remembered is through education, and is why hosting a lecture on Philip Markowicz’s life on campus is so meaningful. For instance, 3GNY has spoken to many different communities — including many high school students — about the Holocaust and intolerance. In doing so, organizations like 3GNY have been able to keep knowledge of the Holocaust alive within the general public.

“I think keeping history present in curriculums is important because of the common saying of ‘don’t let history repeat itself,’” Ruff said.

“I think today’s youth … have a distorted view of history because of the distortion of our media,” Miga said. “And so, I think it’s very important to hear someone like this gentleman.”

At the University of Toledo, education on the Holocaust is also offered through its academics. Philip Markowicz’s family created the Philip Markowicz Endowed Professorship in Judaism and Biblical Studies. Barry Jackisch, a university professor specializing in the study of Germany and the Holocaust, is the current holder of this position.

“…Philip Markowicz was a brilliant Talmud scholar. He really understood, in other words, Jewish religious teaching and biblical study,” Jackisch said. “The family entered into an agreement with the University of Toledo to create an endowed position that would reflect the various experiences that Philip Markowicz and his interests have.”

As part of the professorship, Jackisch gives public talks and brings awareness to the Holocaust and the stories of survivors. He has also worked to enhance Holocaust education throughout the University of Toledo campus and the state of Ohio as a whole.

“I’ve just submitted a new minor in Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Toledo. So that’s in the pipeline to be approved,” Jackisch said. “The longer-term project over the next couple of years is to hopefully develop a continuing education unit program that would be not for current undergraduates, but for in-service teachers … for any teacher in the state of Ohio that was interested in doing more development work in the area of Holocaust studies, it would be fully directed at it.”

Making efforts to allow knowledge of the Holocaust and the stories of Holocaust survivors to remain in public consciousness allows for the most important lesson of the Holocaust to persist: remembering what happens when ordinary people become victims of the perils of intolerance.

“We really cannot forget when hate gets this far, because this is what happens when hate is allowed to permeate through society like this,” Steven Markowicz said.

The Carlson Library has done its part to help preserve the story of one Holocaust survivor. By hosting a lecture discussing the story of Philip Markowicz, the library hopes that it encourages others to do the same and that future generations will continue to share these stories.